Brazilians are currently living in a dystopian landscape.

Thick smoke, oppressive heat and eerily orange sunsets blanket both major cities and small villages. Hundreds of cities are exposed to dangerous levels of air pollution while thousands of hectares of forest burn. The jarring images send out a clear distress signal: Something is fundamentally amiss.

Everybody familiar with the scientific literature understands that climate change is accelerating, manifesting as heatwaves, severe droughts, more frequent floods and devastating fires, leading to urban calamities, biodiversity loss, economic impacts and health hazards. But this spate of fires is truly exceptional. Preliminary analyses by WRI’s Global Forest Watch initiative, which monitors tree cover loss in near-real time through satellite images, show that the current fires season in Brazil is the worst in at least a decade, with more than 47,000 high-confidence fire alerts from the beginning of the year through Sept. 16, 2024. MapBiomas data shows an 85% increase in area affected by fires, compared to the average since 2019.

Conversely, the country is also experiencing bouts of more intense rainfall, with the recent floods in Rio Grande do Sul serving as a distressing example of this trend.

Persistent heat and shifting rainfall patterns, turbocharged by climate change, are normalizing what once were record-breaking fires, floods and landslides in Brazil. The question now is: Will they prompt action?

Brazil Engulfed in Flames

According to Carlos Nobre, a renowned climatologist and leading scientist in Brazil, we are living in a scenario of dread. The nation is currently witnessing the cumulative effects of accelerated climate change, rampant arson and the persistence of an agricultural development model. Unlike other countries, where fires are a natural part of the forest ecosystem, almost all fires in the Amazon and Pantanal regions of Brazil are human-caused. Amid weak regulatory oversight, some rural producers persist in using deforestation and fire to clear land for farms and ranches.

That, plus the hot and dry conditions caused by climate change, are causing fires to rage out of control.

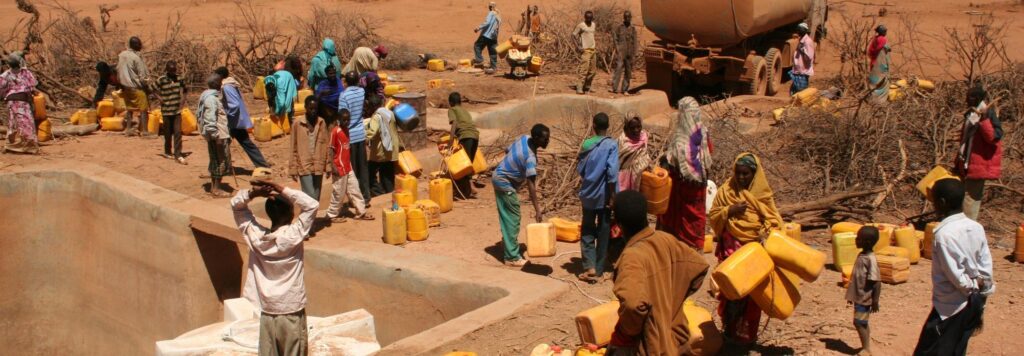

Brazil is currently enduring its longest drought in 70 years, impacting at least 1,400 cities and over 80% of Brazil’s territory . The situation is starkly highlighted by the Madeira River, a major tributary of the Amazon River, which has recorded a water level of just 41 centimeters at the station in Porto Velho, Rondônia — the lowest since 1967, per the Geological Survey of Brazil.

More than 5,000 fires were reported in a single day. The largest city in South America, São Paulo, registered the worst air quality in the world. Brasilia has seen hundreds of people hospitalized with respiratory problems. And since smoke knows no borders, the fires in Brazil have precipitated cross-border environmental issues, affecting neighboring countries like Argentina, Paraguay and Bolivia. Each of these nations is grappling with their own fire outbreaks.

Agribusiness is also suffering. In the state of São Paulo, fire-related damages to the sector are estimated at R$2 billion ($366 million), as reported by the Department of Agriculture and Supply.

And these most recent fires come on top of longer-term environmental threats facing all of Brazil’s major ecosystems. The Cerrado tropical savanna, pressured by agricultural production, is witnessing threats to its biodiversity and the water quality of eight of the 12 major Brazilian river basins that traverse the region. The Pantanal, the world’s largest tropical wetland and largest flooded grasslands, faces dangerously low water levels and potentially the worst drought in its history. Meanwhile, the Amazon, vital for regulating the country’s rainfall, is at risk of irreversible collapse by 2050, according to a recent study published in Nature. This is despite a significant reduction in deforestation rates in the last year.

Brazil Shows Mixed Signals on Environmental Leadership

As Brazil prepares to host the UN Climate Conference (COP 30) in Belém, Pará at the end of 2025, the nation is positioning itself to be a front-runner on the global environmental stage. However, the widespread wildfires cloud the political and diplomatic aspirations of President Lula, who faces scrutiny over the alignment between his rhetoric and his practical agenda for climate action.

This federal administration has made noticeable progress compared to the era of former President Jair Bolsonaro, marked by a significant shift in narrative — from climate denialism to a discourse that values scientific input — and an increase in funding. A prime example is an annual R$63.5 million devoted to fire control and prevention, a 26.2% increase compared to 2022, the last year of Bolsonaro’s term.

Nonetheless, the country has recently sent mixed signals in how it will approach climate and environmental action.

For example, while the federal government recently announced the formation of the Autoridade Climática, or National Climate Authority, the move comes more than a year after the initiative was promised, and its remit remains unclear. Some environmental advocates believe the government should strengthen existing agencies such as the Brazilian Institute of Space Research (INPE), the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), and the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio), suggesting that enhancing their infrastructure and budgets would more effectively meet current environmental challenges.

Amidst severe drought, heat and rampant forest fires, President Lula led his ministers to the most affected areas, demanding decisive action. Yet the government has delayed its timeline for releasing a Supreme Court-mandated plan to prevent and combat fires in the Pantanal and Amazon. Although the court’s order was issued in March, it wasn’t until August that Brazil’s Federal Attorney General’s Office sought an extension to finalize this plan.

Another move that’s drawn criticism is the plan to expand oil exploration in Brazil, particularly along the equatorial margin, located only 500 kilometers from the mouth of the Amazon River. This comes at a time when there is a pressing need for decarbonization policies. Similarly, a plan to pave a segment of the BR-319 highway through the heart of the Amazon, connecting Manaus to Porto Velho, is raising alarms. This development could potentially trigger a surge in deforestation and, as a result, an increase in greenhouse gas emissions, running counter to the government’s stated objective of assuming a global leadership role in addressing the climate crisis.

State and municipal governments in Brazil have also faced criticism. Recently, they have been navigating a precarious balance between unfulfilled promises and reactive measures. The challenge of coordinating and implementing enduring public policies to combat climate change has become more pronounced over the past decade, exacerbated by increasing political polarization and the persistence of traditional agendas in the National Congress. These agendas favor economic systems that are reluctant to adapt to a low-carbon economy and a world urgently requiring a just and rapid transition.

A constructive approach to political coordination in Brazil could involve establishing a comprehensive climate information and data system that integrates federal and subnational networks. Legal safeguards could also be implemented to protect climate services from budgetary reallocations in the Federal Budget Guidelines Act.

Balancing Development with Decarbonization

The task of harmonizing decarbonization with economic development is paramount and increasingly spotlighted in global economic forums, including this year’s G20 summit hosted by Brazil and the upcoming UN climate summit in Baku, Azerbaijan. Brazil has an opportunity to show the world what a low-carbon development model can look like — but only if it takes strong climate action both domestically and internationally.

Brazil is currently developing its new Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), which delineates its greenhouse gas emissions-reduction targets. Brazil has the opportunity to become a global leader by adopting ambitious emissions-reduction targets for 2030 and 2035 that would keep it on track for achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. But the country must ensure its actions consistently reflect its environmental rhetoric to truly advance towards this new paradigm. Recent weeks have shown a lag in timely and effective measures to address the forest fires and climate crises, highlighting a gap between policy and practice.

Moreover, it is crucial for Brazil to incorporate adaptation as a fundamental aspect of its economic and social development strategies to enhance national resilience against the impacts of climate change. Effective multi-level governance is essential to respond to escalating challenges, alongside a commitment to funding these initiatives.

In a world that increasingly appears out of balance, now is the opportune moment for Brazil to seek consensus and hasten its efforts to adapt to this new era of extremes.